You Are Here

Molly Haig

To see the augmented reality experience download the Artivive App and point the camera at the image above. Don’t forget to turn on the sound.

We both left Boston last fall. She had to, to comply with visa laws. I wanted to, to test out life in New York City. We thought of returning sooner (her) or later (me), but as the world spluttered to a halt, our place-based plans got messier. We’ve been away almost a year, but this is not where we imagined we’d be.

Emptiness is a feeling of dislocation, I write, thinking about the location part of the word. Dasha imagines empty or emptying spaces: a black hole, field of quicksand, a big room without an echo. I say, I feel it most when I expect to feel connected but don’t. Dasha says, we’re creating space for emptiness by wanting something.

In New York City, my mind is in typography-on-the-street mode. My phone is crammed with snapshots of storefront signage and sidewalk trash. I love noticing what others pass without a glance. Existing in the city’s language makes me feel like I’m really there. When Covid-19 hits and I leave for clean, rural Vermont, I wonder: without the detritus of other people’s words, how can I orient myself?

On a podcast just audible above my clinking dinner dishes, design critic Jessica Helfand asks this too: “[If] you don’t have the patterns and the behaviors and the systems by which you previously worked, what do you have? Who are you as a fully formed individual in the world, to ask questions by yourself, and then go from there?” I am reassured to know that others are wondering this, but don’t know the answer. Location seems essential, so I cling to the structure of being a designer based in New York City, although I am not.

Dasha and I wonder: how does emptiness relate to place? But we answer differently. A place that you are (but don’t want to be) feels empty for lack of something you had in the past, say I, who can legally live anywhere in the US, but somehow still feel unmoored.

A place that you can’t be (and miss) is empty for lack of you, says Dasha, who can’t return to the home where she built her adult life. Emptiness connects to place, we agree, when our freedom (to leave or return, to be alone or together, to think, to pursue goals) feels limited. But we also agree that geography is not fully culpable, and that even in our unplanned spots, we are not helpless.

For Lines Through, my project is in conversation with James Barkley’s serene portrait of a dancer near a window in a sunlit studio. To my mind, the photograph invites questions: how does the sunlight feel on his eyelids? Is the studio warm? Did he mean to echo the shadows’ lines with his? What dancers have danced at that barre? Is there 15 years’ accumulation of dust and carpet bits under the heater? Does it smell like Marley? Like sweat? Did the camera’s click echo? Wondering puts me there in the studio.

I want to exist in place as James’ dancer does. He is a participant in his surroundings, basking in the mid-afternoon sunlight, dancing in a room made for dance. I also want to exist in place as I did the moment I became curious about the scene. I want to notice, and I want to do it even when the place I’m noticing is not the place I planned to be in, and when my surroundings don’t fit into a neat framework of what I’ve told myself (as designer, dancer, language-fanatic) to see.

We are the bridge between all of our experiences. They don’t go away if we change location, says Dasha, comforting us both. We are learning to rethink our relationship to place in this time of solitary meals and disrupted plans.

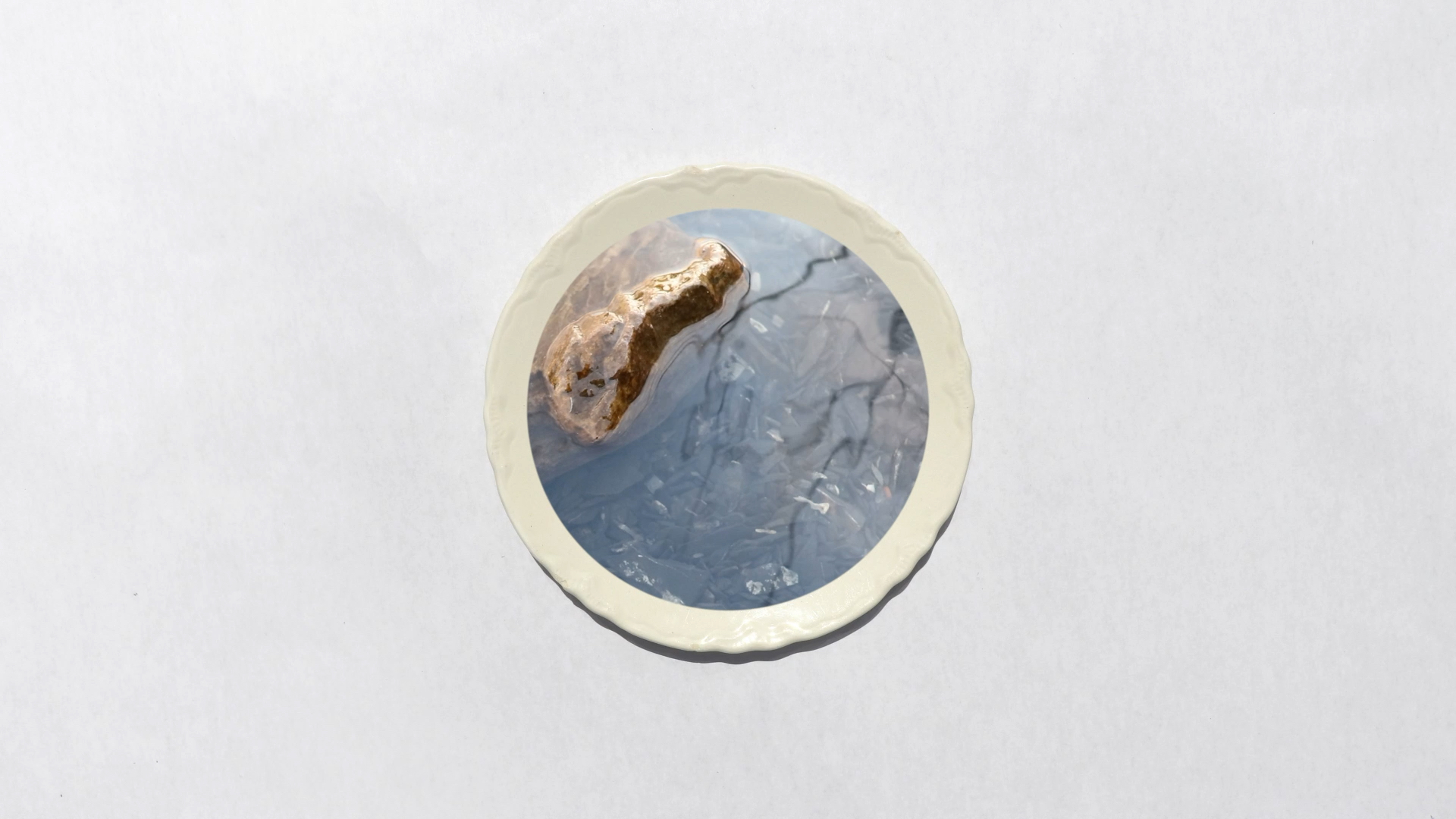

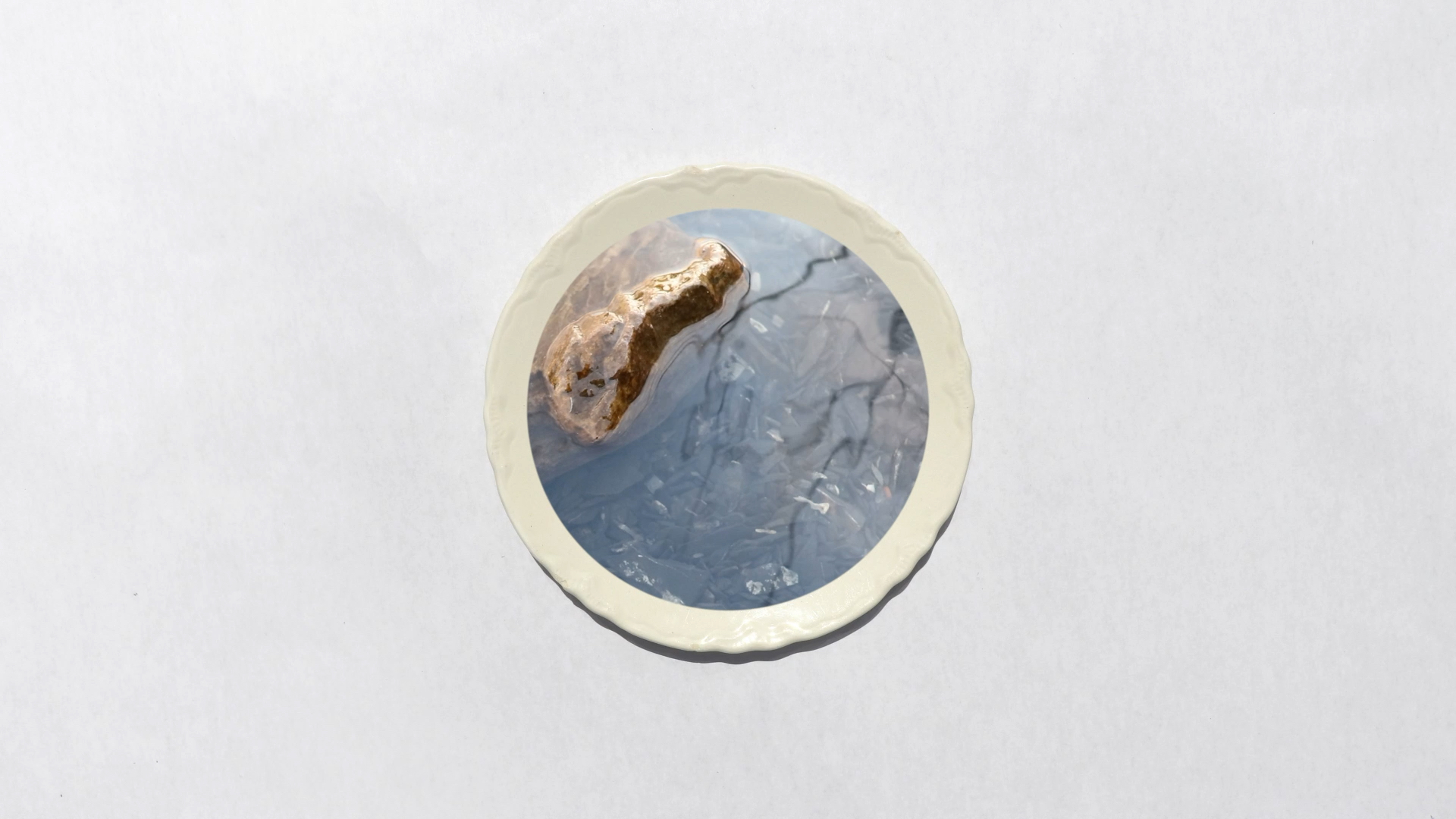

I usually make things about words, but You Are Here is a project without them: a cup of shale, a pot of foam, a plate of lake. These compositions are monuments to my actual surroundings. They are what is here.

Emptiness is a feeling of dislocation, I write, thinking about the location part of the word. Dasha imagines empty or emptying spaces: a black hole, field of quicksand, a big room without an echo. I say, I feel it most when I expect to feel connected but don’t. Dasha says, we’re creating space for emptiness by wanting something.

In New York City, my mind is in typography-on-the-street mode. My phone is crammed with snapshots of storefront signage and sidewalk trash. I love noticing what others pass without a glance. Existing in the city’s language makes me feel like I’m really there. When Covid-19 hits and I leave for clean, rural Vermont, I wonder: without the detritus of other people’s words, how can I orient myself?

On a podcast just audible above my clinking dinner dishes, design critic Jessica Helfand asks this too: “[If] you don’t have the patterns and the behaviors and the systems by which you previously worked, what do you have? Who are you as a fully formed individual in the world, to ask questions by yourself, and then go from there?” I am reassured to know that others are wondering this, but don’t know the answer. Location seems essential, so I cling to the structure of being a designer based in New York City, although I am not.

Dasha and I wonder: how does emptiness relate to place? But we answer differently. A place that you are (but don’t want to be) feels empty for lack of something you had in the past, say I, who can legally live anywhere in the US, but somehow still feel unmoored.

A place that you can’t be (and miss) is empty for lack of you, says Dasha, who can’t return to the home where she built her adult life. Emptiness connects to place, we agree, when our freedom (to leave or return, to be alone or together, to think, to pursue goals) feels limited. But we also agree that geography is not fully culpable, and that even in our unplanned spots, we are not helpless.

For Lines Through, my project is in conversation with James Barkley’s serene portrait of a dancer near a window in a sunlit studio. To my mind, the photograph invites questions: how does the sunlight feel on his eyelids? Is the studio warm? Did he mean to echo the shadows’ lines with his? What dancers have danced at that barre? Is there 15 years’ accumulation of dust and carpet bits under the heater? Does it smell like Marley? Like sweat? Did the camera’s click echo? Wondering puts me there in the studio.

I want to exist in place as James’ dancer does. He is a participant in his surroundings, basking in the mid-afternoon sunlight, dancing in a room made for dance. I also want to exist in place as I did the moment I became curious about the scene. I want to notice, and I want to do it even when the place I’m noticing is not the place I planned to be in, and when my surroundings don’t fit into a neat framework of what I’ve told myself (as designer, dancer, language-fanatic) to see.

We are the bridge between all of our experiences. They don’t go away if we change location, says Dasha, comforting us both. We are learning to rethink our relationship to place in this time of solitary meals and disrupted plans.

I usually make things about words, but You Are Here is a project without them: a cup of shale, a pot of foam, a plate of lake. These compositions are monuments to my actual surroundings. They are what is here.

You Are Here

Molly Haig

To see the augmented reality experience download the Artivive App and point the camera at the image above. Don’t forget to turn on the sound.

We both left Boston last fall. She had to, to comply with visa laws. I wanted to, to test out life in New York City. We thought of returning sooner (her) or later (me), but as the world spluttered to a halt, our place-based plans got messier. We’ve been away almost a year, but this is not where we imagined we’d be.

Emptiness is a feeling of dislocation, I write, thinking about the location part of the word. Dasha imagines empty or emptying spaces: a black hole, field of quicksand, a big room without an echo. I say, I feel it most when I expect to feel connected but don’t. Dasha says, we’re creating space for emptiness by wanting something.

In New York City, my mind is in typography-on-the-street mode. My phone is crammed with snapshots of storefront signage and sidewalk trash. I love noticing what others pass without a glance. Existing in the city’s language makes me feel like I’m really there. When Covid-19 hits and I leave for clean, rural Vermont, I wonder: without the detritus of other people’s words, how can I orient myself?

On a podcast just audible above my clinking dinner dishes, design critic Jessica Helfand asks this too: “[If] you don’t have the patterns and the behaviors and the systems by which you previously worked, what do you have? Who are you as a fully formed individual in the world, to ask questions by yourself, and then go from there?” I am reassured to know that others are wondering this, but don’t know the answer. Location seems essential, so I cling to the structure of being a designer based in New York City, although I am not.

Dasha and I wonder: how does emptiness relate to place? But we answer differently. A place that you are (but don’t want to be) feels empty for lack of something you had in the past, say I, who can legally live anywhere in the US, but somehow still feel unmoored.

A place that you can’t be (and miss) is empty for lack of you, says Dasha, who can’t return to the home where she built her adult life. Emptiness connects to place, we agree, when our freedom (to leave or return, to be alone or together, to think, to pursue goals) feels limited. But we also agree that geography is not fully culpable, and that even in our unplanned spots, we are not helpless.

For Lines Through, my project is in conversation with James Barkley’s serene portrait of a dancer near a window in a sunlit studio. To my mind, the photograph invites questions: how does the sunlight feel on his eyelids? Is the studio warm? Did he mean to echo the shadows’ lines with his? What dancers have danced at that barre? Is there 15 years’ accumulation of dust and carpet bits under the heater? Does it smell like Marley? Like sweat? Did the camera’s click echo? Wondering puts me there in the studio.

I want to exist in place as James’ dancer does. He is a participant in his surroundings, basking in the mid-afternoon sunlight, dancing in a room made for dance. I also want to exist in place as I did the moment I became curious about the scene. I want to notice, and I want to do it even when the place I’m noticing is not the place I planned to be in, and when my surroundings don’t fit into a neat framework of what I’ve told myself (as designer, dancer, language-fanatic) to see.

We are the bridge between all of our experiences. They don’t go away if we change location, says Dasha, comforting us both. We are learning to rethink our relationship to place in this time of solitary meals and disrupted plans.

I usually make things about words, but You Are Here is a project without them: a cup of shale, a pot of foam, a plate of lake. These compositions are monuments to my actual surroundings. They are what is here.

Emptiness is a feeling of dislocation, I write, thinking about the location part of the word. Dasha imagines empty or emptying spaces: a black hole, field of quicksand, a big room without an echo. I say, I feel it most when I expect to feel connected but don’t. Dasha says, we’re creating space for emptiness by wanting something.

In New York City, my mind is in typography-on-the-street mode. My phone is crammed with snapshots of storefront signage and sidewalk trash. I love noticing what others pass without a glance. Existing in the city’s language makes me feel like I’m really there. When Covid-19 hits and I leave for clean, rural Vermont, I wonder: without the detritus of other people’s words, how can I orient myself?

On a podcast just audible above my clinking dinner dishes, design critic Jessica Helfand asks this too: “[If] you don’t have the patterns and the behaviors and the systems by which you previously worked, what do you have? Who are you as a fully formed individual in the world, to ask questions by yourself, and then go from there?” I am reassured to know that others are wondering this, but don’t know the answer. Location seems essential, so I cling to the structure of being a designer based in New York City, although I am not.

Dasha and I wonder: how does emptiness relate to place? But we answer differently. A place that you are (but don’t want to be) feels empty for lack of something you had in the past, say I, who can legally live anywhere in the US, but somehow still feel unmoored.

A place that you can’t be (and miss) is empty for lack of you, says Dasha, who can’t return to the home where she built her adult life. Emptiness connects to place, we agree, when our freedom (to leave or return, to be alone or together, to think, to pursue goals) feels limited. But we also agree that geography is not fully culpable, and that even in our unplanned spots, we are not helpless.

For Lines Through, my project is in conversation with James Barkley’s serene portrait of a dancer near a window in a sunlit studio. To my mind, the photograph invites questions: how does the sunlight feel on his eyelids? Is the studio warm? Did he mean to echo the shadows’ lines with his? What dancers have danced at that barre? Is there 15 years’ accumulation of dust and carpet bits under the heater? Does it smell like Marley? Like sweat? Did the camera’s click echo? Wondering puts me there in the studio.

I want to exist in place as James’ dancer does. He is a participant in his surroundings, basking in the mid-afternoon sunlight, dancing in a room made for dance. I also want to exist in place as I did the moment I became curious about the scene. I want to notice, and I want to do it even when the place I’m noticing is not the place I planned to be in, and when my surroundings don’t fit into a neat framework of what I’ve told myself (as designer, dancer, language-fanatic) to see.

We are the bridge between all of our experiences. They don’t go away if we change location, says Dasha, comforting us both. We are learning to rethink our relationship to place in this time of solitary meals and disrupted plans.

I usually make things about words, but You Are Here is a project without them: a cup of shale, a pot of foam, a plate of lake. These compositions are monuments to my actual surroundings. They are what is here.